Optic Nerve Atrophy

- Publicado en Ophthalmology Rehabilitation Center, Services

- Publicado en Ophthalmology Rehabilitation Center, Services

Osteoporosis

OSTEOPOROSIS

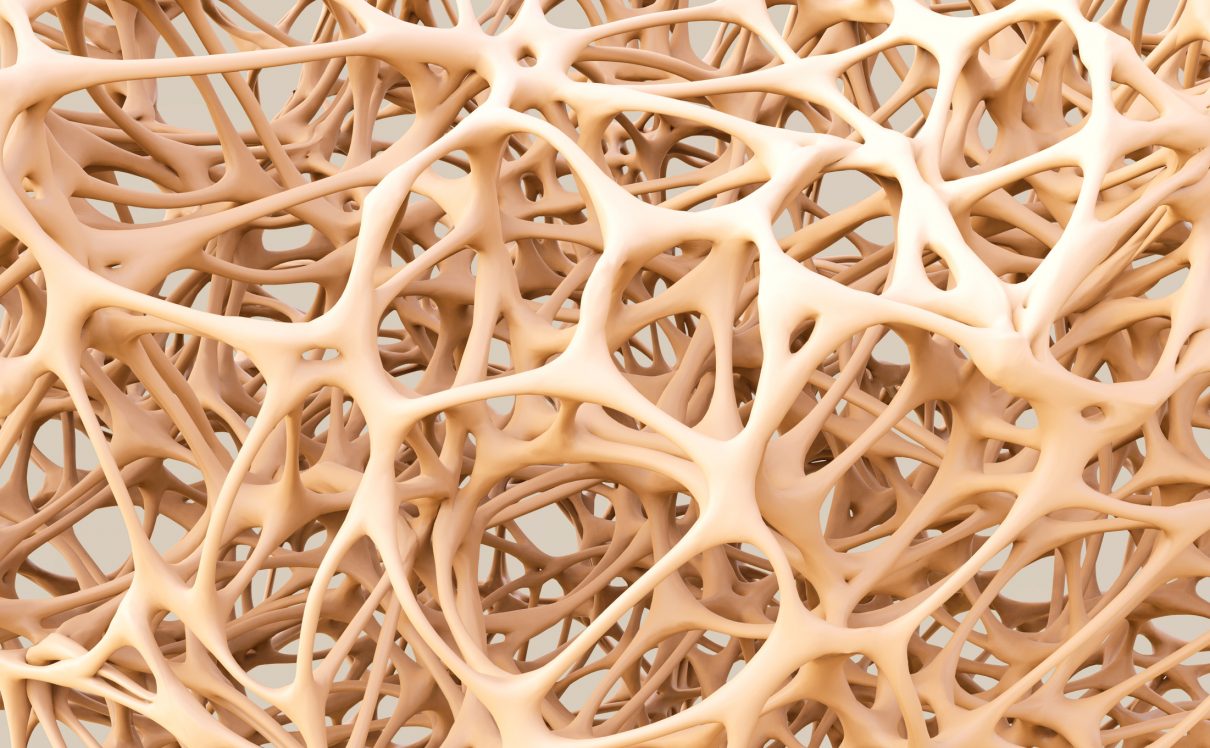

Introduction: Osteoporosis, which literally means porous bone, is a disease in which the density and quality of bone are reduced. As bones become more porous and fragile, the risk of fracture is greatly increased. The loss of bone occurs silently and progressively. Often there are no symptoms until the first fracture occurs.

Osteoporosis affects men and women of all races. But white and Asian women — especially older women who are past menopause — are at highest risk. Medications, healthy diet and weight-bearing exercise can help prevent bone loss or strengthen already weak bones.

As we age some of our bone cells begin to dissolve bone matrix (resorption), while new bone cells deposit osteoid (formation). This process is known as remodeling.

For people with osteoporosis, bone loss outpaces the growth of new bone. Bones become porous, brittle and prone to fracture. Around the world, 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men aged fifty years and over are at risk of an osteoporotic fracture. In fact, an osteoporotic fracture is estimated to occur every 3 seconds. The most common fractures associated with osteoporosis occur at the hip, spine and wrist. The likelihood of these fractures occurring, particularly at the hip and spine, increases with age in both women and men.

Of particular concern are vertebral (spinal) and hip fractures. Vertebral fractures can result in serious consequences, including loss of height, intense back pain and deformity (sometimes called Dowager’s Hump). A hip fracture often requires surgery and may result in loss of independence or death.

Cause

- The loss of estrogen due to menopause is the most common cause of osteoporosis. In fact, 25% of women older than 60 years old are found to have osteoporosis.

- Women who go through menopauseearly or those who have had their ovaries surgically removed before the age of 45 are at risk.

The aging process is a major factor because, by the age of 50, bones start thinning by 1-3% every year.

Unchangeable risks

Some risk factors for osteoporosis are out of your control, including:

- Your sex. Women are much more likely to develop osteoporosis than are men.

- Age. The older you get, the greater your risk of osteoporosis.

- Race. You’re at greatest risk of osteoporosis if you’re white or of Asian descent.

- Family history. Having a parent or sibling with osteoporosis puts you at greater risk, especially if your mother or father fractured a hip.

- Body frame size. Men and women who have small body frames tend to have a higher risk because they might have less bone mass to draw from as they age.

Hormone levels

Osteoporosis is more common in people who have too much or too little of certain hormones in their bodies. Examples include:

- Sex hormones. Lowered sex hormone levels tend to weaken bone. The reduction of estrogen levels in women at menopause is one of the strongest risk factors for developing osteoporosis.

Men have a gradual reduction in testosterone levels as they age. Treatments for prostate cancer that reduce testosterone levels in men and treatments for breast cancer that reduce estrogen levels in women are likely to accelerate bone loss.

- Thyroid problems. Too much thyroid hormone can cause bone loss. This can occur if your thyroid is overactive or if you take too much thyroid hormone medication to treat an underactive thyroid.

- Other glands. Osteoporosis has also been associated with overactive parathyroid and adrenal glands.

Dietary factors

Osteoporosis is more likely to occur in people who have:

- Low calcium intake. A lifelong lack of calcium plays a role in the development of osteoporosis. Low calcium intake contributes to diminished bone density, early bone loss and an increased risk of fractures.

- Eating disorders. Severely restricting food intake and being underweight weakens bone in both men and women.

- Gastrointestinal surgery. Surgery to reduce the size of your stomach or to remove part of the intestine limits the amount of surface area available to absorb nutrients, including calcium. These surgeries include those to help you lose weight and for other gastrointestinal disorders.

Steroids and other medications

Long-term use of oral or injected corticosteroid medications, such as prednisone and cortisone, interferes with the bone-rebuilding process. Osteoporosis has also been associated with medications used to combat or prevent:

- Seizures

- Gastric reflux

- Cancer

- Transplant rejection

Medical conditions

The risk of osteoporosis is higher in people who have certain medical problems, including:

- Celiac disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Kidney or liver disease

- Cancer

- Lupus

- Multiple myeloma

- Rheumatoid arthritis

Lifestyle choices

Some bad habits can increase your risk of osteoporosis. Examples include:

- Sedentary lifestyle. People who spend a lot of time sitting have a higher risk of osteoporosis than do those who are more active. Any weight-bearing exercise and activities that promote balance and good posture are beneficial for your bones, but walking, running, jumping, dancing and weightlifting seem particularly helpful.

- Excessive alcohol consumption. Regular consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks a day increases your risk of osteoporosis.

- Tobacco use. The exact role tobacco plays in osteoporosis isn’t clear, but it has been shown that tobacco use contributes to weak bones.

Common risk factors

- A family history of osteoporosis

- European or Asian lineage

- Lack of vitamin D or calcium

- Regular consumption of alcohol or caffeine

- Smoking

- Sharp decreases in weight due to excessive exercising or dieting

- Overuse of steroids

- Conditions such as hormonal imbalances or thyroid disease

Chronic diseases such as liver disease or gastrointestinal disorders

Complications

Compression fractures

The bones that make up your spine (vertebrae) can weaken to the point that they crumple, which may result in back pain, lost height and a hunched posture.

Bone fractures, particularly in the spine or hip, are the most serious complications of osteoporosis. Hip fractures often are caused by a fall and can result in disability and even an increased risk of death within the first year after the injury.

In some cases, spinal fractures can occur even if you haven’t fallen. The bones that make up your spine (vertebrae) can weaken to the point of crumpling, which can result in back pain, lost height and a hunched forward posture.

Sign and Symptom: There typically are no symptoms in the early stages of bone loss. But once your bones have been weakened by osteoporosis, you might have signs and symptoms that include:

- Back pain, caused by a fractured or collapsed vertebra

- Loss of height over time

- A stooped posture

- A bone that breaks much more easily than expected

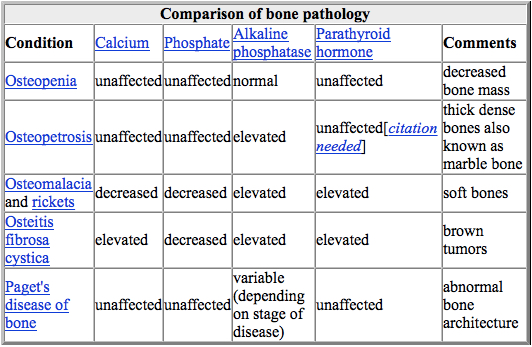

Diagnosis: The diagnosis of osteoporosis can be made using conventional radiography and by measuring the bone mineral density (BMD).[79] The most popular method of measuring BMD is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

In addition to the detection of abnormal BMD, the diagnosis of osteoporosis requires investigations into potentially modifiable underlying causes; this may be done with blood tests. Depending on the likelihood of an underlying problem, investigations for cancer with metastasis to the bone, multiple myeloma, Cushing’s disease and other above-mentioned causes may be performed.

Conventional radiography[edit]

Conventional radiography is useful, both by itself and in conjunction with CT or MRI, for detecting complications of osteopenia (reduced bone mass; pre-osteoporosis), such as fractures; for differential diagnosis of osteopenia; or for follow-up examinations in specific clinical settings, such as soft tissue calcifications, secondary hyperparathyroidism, or osteomalacia in renal osteodystrophy. However, radiography is relatively insensitive to detection of early disease and requires a substantial amount of bone loss (about 30%) to be apparent on X-ray images.

The main radiographic features of generalized osteoporosis are cortical thinning and increased radiolucency. Frequent complications of osteoporosis are vertebral fractures for which spinal radiography can help considerably in diagnosis and follow-up. Vertebral height measurements can objectively be made using plain-film X-rays by using several methods such as height loss together with area reduction, particularly when looking at vertical deformity in T4-L4, or by determining a spinal fracture index that takes into account the number of vertebrae involved. Involvement of multiple vertebral bodies leads to kyphosis of the thoracic spine, leading to what is known as dowager’s hump.

Dual-energy X-ray[edit]

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA scan) is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is diagnosed when the bone mineral density is less than or equal to 2.5 standard deviations below that of a young (30–40-year-old[4]:58), healthy adult women reference population. This is translated as a T-score. But because bone density decreases with age, more people become osteoporotic with increasing age.[4]:58 The World Health Organization has established the following diagnostic guidelines:[4][20]

| Category | T-score range | % young women |

| Normal | T-score ≥ −1.0 | 85% |

| Osteopenia | −2.5 < T-score < −1.0 | 14% |

| Osteoporosis | T-score ≤ −2.5 | 0.6% |

| Severe osteoporosis | T-score ≤ −2.5 with fragility fracture[20] |

The International Society for Clinical Densitometry takes the position that a diagnosis of osteoporosis in men under 50 years of age should not be made on the basis of densitometric criteria alone. It also states, for premenopausal women, Z-scores (comparison with age group rather than peak bone mass) rather than T-scores should be used, and the diagnosis of osteoporosis in such women also should not be made on the basis of densitometric criteria alone.[80]

Biomarkers

Chemical biomarkers are a useful tool in detecting bone degradation. The enzyme cathepsin K breaks down type-I collagen, an important constituent in bones. Prepared antibodies can recognize the resulting fragment, called a neoepitope, as a way to diagnose osteoporosis.[81] Increased urinary excretion of C-telopeptides, a type-I collagen breakdown product, also serves as a biomarker for osteoporosis.[82]

Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) differs from DXA in that it gives separate estimates of BMD for trabecular and cortical bone and reports precise volumetric mineral density in mg/cm3 rather than BMD’s relative Z-score. Among QCT’s advantages: it can be performed at axial and peripheral sites, can be calculated from existing CT scans without a separate radiation dose, is sensitive to change over time, can analyze a region of any size or shape, excludes irrelevant tissue such as fat, muscle, and air, and does not require knowledge of the patient’s subpopulation in order to create a clinical score (e.g. the Z-score of all females of a certain age). Among QCT’s disadvantages: it requires a high radiation dose compared to DXA, CT scanners are large and expensive, and because its practice has been less standardized than BMD, its results are more operator-dependent. Peripheral QCT has been introduced to improve upon the limitations of DXA and QCT.[79]

Quantitative ultrasound has many advantages in assessing osteoporosis. The modality is small, no ionizing radiation is involved, measurements can be made quickly and easily, and the cost of the device is low compared with DXA and QCT devices. The calcaneus is the most common skeletal site for quantitative ultrasound assessment because it has a high percentage of trabecular bone that is replaced more often than cortical bone, providing early evidence of metabolic change. Also, the calcaneus is fairly flat and parallel, reducing repositioning errors. The method can be applied to children, neonates, and preterm infants, just as well as to adults.[79] Some ultrasound devices can be used on the tibia

Treatment: Treatment recommendations are often based on an estimate of your risk of breaking a bone in the next 10 years using information such as the bone density test. If your risk isn’t high, treatment might not include medication and might focus instead on modifying risk factors for bone loss and falls.

Biophosphonates

For both men and women at increased risk of fracture, the most widely prescribed osteoporosis medications are bisphosphonates. Examples include:

- Alendronate (Binosto, Fosamax)

- Risedronate (Actonel, Atelvia)

- Ibandronate (Boniva)

- Zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa)

Side effects include nausea, abdominal pain and heartburn-like symptoms. These are less likely to occur if the medicine is taken properly.

Intravenous forms of bisphosphonates don’t cause stomach upset but can cause fever, headache and muscle aches for up to three days. It might be easier to schedule a quarterly or yearly injection than to remember to take a weekly or monthly pill, but it can be more costly to do so.

Monoclonal antibody medications

Compared with bisphosphonates, denosumab (Prolia, Xgeva) produces similar or better bone density results and reduces the chance of all types of fractures. Denosumab is delivered via a shot under the skin every six months.

If you take denosumab, you might have to continue to do so indefinitely. Recent research indicates there could be a high risk of spinal column fractures after stopping the drug.

A very rare complication of bisphosphonates and denosumab is a break or crack in the middle of the thighbone.

A second rare complication is delayed healing of the jawbone (osteonecrosis of the jaw). This can occur after an invasive dental procedure such as removing a tooth.

You should have a dental examination before starting these medications, and you should continue to take good care of your teeth and see your dentist regularly while on them. Make sure your dentist knows that you’re taking these medications.

Hormone-related therapy

Estrogen, especially when started soon after menopause, can help maintain bone density. However, estrogen therapy can increase the risk of blood clots, endometrial cancer, breast cancer and possibly heart disease. Therefore, estrogen is typically used for bone health in younger women or in women whose menopausal symptoms also require treatment.

Raloxifene (Evista) mimics estrogen’s beneficial effects on bone density in postmenopausal women, without some of the risks associated with estrogen. Taking this drug can reduce the risk of some types of breast cancer. Hot flashes are a common side effect. Raloxifene also may increase your risk of blood clots.

In men, osteoporosis might be linked with a gradual age-related decline in testosterone levels. Testosterone replacement therapy can help improve symptoms of low testosterone, but osteoporosis medications have been better studied in men to treat osteoporosis and thus are recommended alone or in addition to testosterone.

Bone-building medications

If you can’t tolerate the more common treatments for osteoporosis — or if they don’t work well enough — your doctor might suggest trying:

- Teriparatide (Forteo). This powerful drug is similar to parathyroid hormone and stimulates new bone growth. It’s given by daily injection under the skin. After two years of treatment with teriparatide, another osteoporosis drug is taken to maintain the new bone growth.

- Abaloparatide (Tymlos) is another drug similar to parathyroid hormone. You can take it for only two years, which will be followed by another osteoporosis medication.

- Romosozumab (Evenity). This is the newest bone-building medication to treat osteoporosis. It is given as an injection every month at your doctor’s office. It is limited to one year of treatment, followed by other osteoporosis medications

A new stem cell review

We have talked about how recent progress has been made in treating this disease by removing senescent cells in mice. In this new review, the authors take a look at delivering stem cells to the bone tissue to try to address the imbalance[1].

The idea of increasing the numbers of bone-building stem cells and replacing those lost with age is a plausible approach.

However, this approach is far from complete, as it only addresses one aspect of osteoporosis that causes bones to weaken. Replacing lost stem cells alone is unlikely to solve the problem, as the underlying causes, such as senescent cell accumulation and resulting inflammation, are not being addressed.

Conclusion

As the authors here mention, there are many current stem cell trials, in which researchers are investigating other diseases, that may influence the progression of osteoporosis. This gives us the chance to learn a great deal about stem cell therapies for osteoporosis with some additional effort.

It is plausible that the combination of senescent cell removal therapies and stem cell therapy could be a potent force in treating osteoporosis. Indeed, we have recently seen that reducing chronic age-related inflammation helps to improve stem cell transplants in a recent study.

Prevention

Good nutrition and regular exercise are essential for keeping your bones healthy throughout your life.

Protein

Protein is one of the building blocks of bone. However, there’s conflicting evidence about the impact of protein intake on bone density.

Most people get plenty of protein in their diets, but some do not. Vegetarians and vegans can get enough protein in the diet if they intentionally seek suitable sources, such as soy, nuts, legumes, seeds for vegans and vegetarians, and dairy and eggs for vegetarians.

Older adults might eat less protein for various reasons. If you think you’re not getting enough protein, ask your doctor if supplementation is an option.

Body weight

Being underweight increases the chance of bone loss and fractures. Excess weight is now known to increase the risk of fractures in your arm and wrist. As such, maintaining an appropriate body weight is good for bones just as it is for health in general.

Calcium

Men and women between the ages of 18 and 50 need 1,000 milligrams of calcium a day. This daily amount increases to 1,200 milligrams when women turn 50 and men turn 70.

Good sources of calcium include:

- Low-fat dairy products

- Dark green leafy vegetables

- Canned salmon or sardines with bones

- Soy products, such as tofu

- Calcium-fortified cereals and orange juice

If you find it difficult to get enough calcium from your diet, consider taking calcium supplements. However, too much calcium has been linked to kidney stones. Although yet unclear, some experts suggest that too much calcium especially in supplements can increase the risk of heart disease.

The Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) recommends that total calcium intake, from supplements and diet combined, should be no more than 2,000 milligrams daily for people older than 50.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D improves your body’s ability to absorb calcium and improves bone health in other ways. People can get some of their vitamin D from sunlight, but this might not be a good source if you live in a high latitude, if you’re housebound, or if you regularly use sunscreen or avoid the sun because of the risk of skin cancer.

To get enough vitamin D to maintain bone health, it’s recommended that adults ages 51 to 70 get 600 international units (IU) and 800 IU a day after age 70 through food or supplements.

People without other sources of vitamin D and especially with limited sun exposure might need a supplement. Most multivitamin products contain between 600 and 800 IU of vitamin D. Up to 4,000 IU of vitamin D a day is safe for most people.

Exercise

Exercise can help you build strong bones and slow bone loss. Exercise will benefit your bones no matter when you start, but you’ll gain the most benefits if you start exercising regularly when you’re young and continue to exercise throughout your life.

Combine strength training exercises with weight-bearing and balance exercises. Strength training helps strengthen muscles and bones in your arms and upper spine. Weight-bearing exercises — such as walking, jogging, running, stair climbing, skipping rope, skiing and impact-producing sports — affect mainly the bones in your legs, hips and lower spine. Balance exercises such as tai chi can reduce your risk of falling especially as you get older.

Swimming, cycling and exercising on machines such as elliptical trainers can provide a good cardiovascular workout, but they don’t improve bone health.

- Publicado en Ophthalmology Rehabilitation Center, Services

English

English  ไทย

ไทย  繁體中文

繁體中文  العربية

العربية  Português

Português